A Path Forward

Below is an essay I wrote for my Postmodern Fictions class on Austerlitz and the nature of memory. As always, I’d love to hear any feedback.

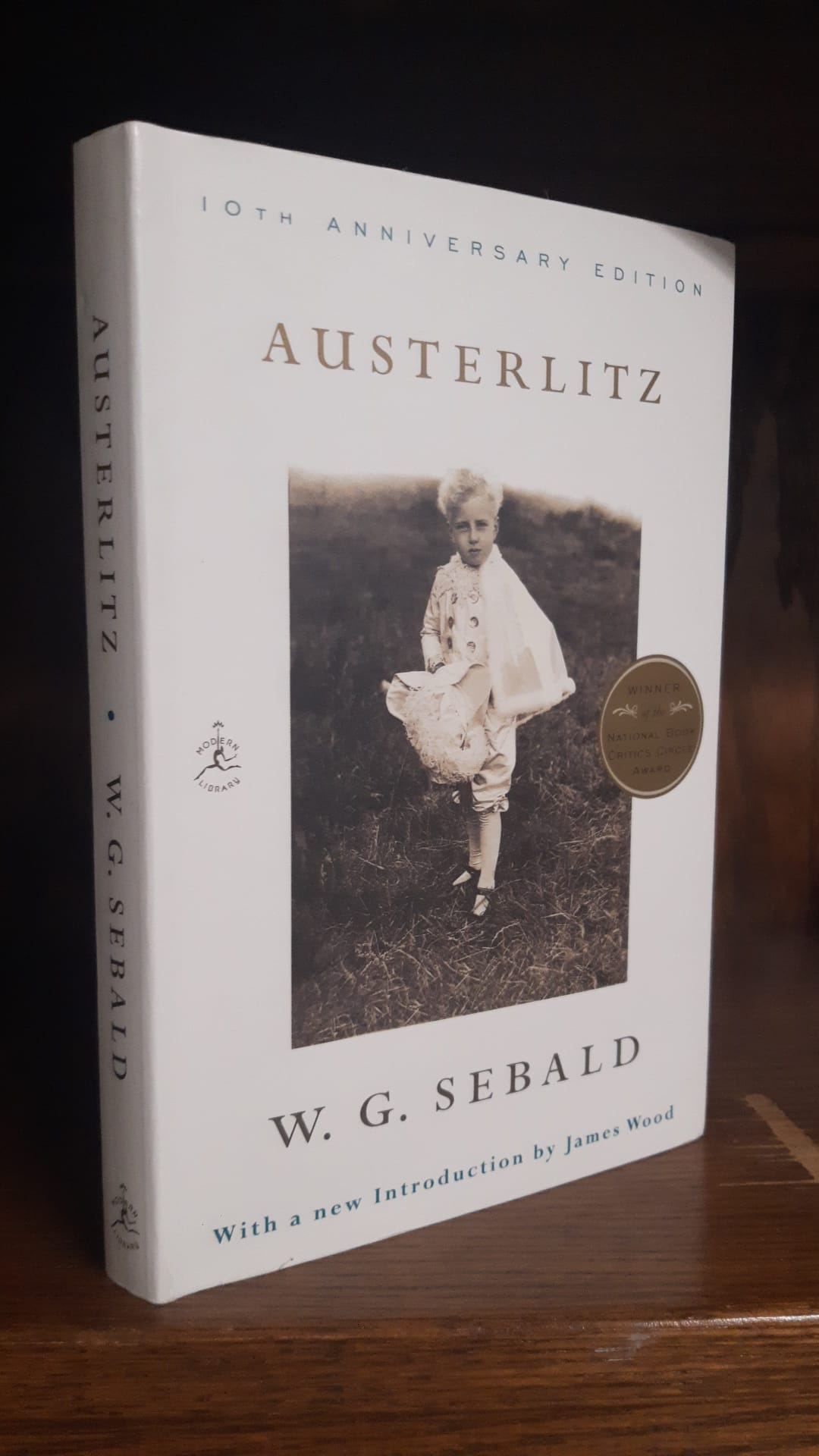

Memory is tricky and no one is more aware of this than W. G. Sebald. Austerlitz, written by Sebald, is an exploration of memory and the radical uncertainty that comes along with it. From the very way Sebald chooses to tell the story, to the individual “memories” the narrator in the story relates, there is so much to learn about the nature of memory. The idea that memory is fallible is not new, but the ways it is conveyed are eye-opening. Throughout Austerlitz, Sebald expresses how problematic memory can be, yet in some respects gives an approach to how to deal with that fact in the way Austerlitz is written and the many times through the narrator Sebald calls out the very problems of memory. By calling attention to and demonstrating all of the problems with memory, Sebald actually provides a path forward.

Austerlitz is written in an unconventional manner. There are no paragraphs or chapters, just one long stream of consciousness as if the narrator were remembering it right then. “And now in writing this, I do remember that such an idea occurred to me at the time–as if…” (p. 24) Sebald writes the book in an atypical stream-of-consciousness manner. Rather than being in a character’s mind as the story unfolds, Sebald writes the unnamed narrator’s stream of consciousness not in the moment of the story, but as the narrator is writing it years later, “And now in writing this, I do remember…” as opposed to a narration at the moment itself. Additionally, at one point it flips from the narrator’s perspective “Having said this Austerlitz fell silent, and for a while, it seemed to me, he gazed into the farthest distance. Since my childhood and youth, he finally began, looking at me again…” (p. 44) to Austerlitz’s “...looking at me again, I have never known who I really was. From where I stand now, of course, I can see that…,” (p. 44) and for the remainder of the book, it continues in the same manner. Sebald writes in a similar stream-of-consciousness style, but uses I statements and conveys Austerlitz’s perspective in the same manner as the narrator’s. To complicate things even further, once Sebald switches to Austerlitz’s perspective, he still interjects and reminds the reader that this story is being told to the narrator by Austerlitz. “I remember, said Austerlitz, that in the…” (p. 135) and, “as far as I could see, said Austerlitz, the …” (p. 194). As convoluted as this may seem, Sebald is in many ways telling the story in the most accurate and real way possible. If this were a nonfiction book, which it is not, and Sebald was writing a personal narrative in the most accurate way he could, this would be the way to do it. Sebald is writing the story as the narrator remembers it at the time of the writing, without implying that it is completely accurate. It is simply written the way the narrator remembers it at the moment.

Beyond the broader way the book is written, Sebald explores memory in a variety of ways. From the very beginning of the book on page four, the issue of memory is clearly front and center.

I cannot now recall exactly what creatures I saw on that visit to the Antwerp Nocturama, but there were probably bats and jerboas from Egypt and the Gobi Desert, native European hedgehogs and owls, Australian opossums, pine martens, dormice, and lemurs, leaping from branch to branch, darting back and forth over the grayish-yellow sandy ground, or disappearing into a bamboo thicket. The only animal which has remained lingering in my memory is the raccoon. … Otherwise, all I remember of the denizens of the Nocturama is that several of them had strikingly large eyes…

There is so much to unpack within this one quote. The first aspect that caught my attention is the obvious contradiction that occurs almost immediately. First, Sebald says, “I cannot now recall exactly what creatures I saw…” and then goes on to list many very specific animals, “bats and jerboas…native European hedgehogs and owls, Australian opossums…” Sebald is clearly demonstrating the odd way memory works. While the narrator does not remember any individual animal, they have a sense of what was likely in this Nocturama “...but there were probably bats and jerboas…” without knowing for certain what was there. To quote S. E. Grove, “memory is a tricky thing…”

Examining the block quote, there is another very relevant point. The narrator’s memory is clearly fickle, nevertheless, they are attempting to tell the most accurate story they can construct from that day. Sebald is showing the reader that while memory itself may be unreliable and riddled with missing parts and vague impressions, there is a way to convey this that shows the uncertainty inherent to memory while still being accurate. Instead of pretending that the narrator remembered all of those animals, the narrator tells the reader, “I cannot now recall…” indicating that while his memory is not completely reliable, he is “reliably unreliable.” The narrator will tell the reader whenever something is not clear to them. In addition, the manner in which the narrator related the memory seemed to be hyperrealistic to the way the narrator would be remembering it if they were writing it down at that exact moment. They begin with “I cannot now recall…” but goes on to list many animals as someone that was recounting a story to a friend would. “There was this time when I went to the zoo, now I don’t remember the exact animals, but there were giraffes, zebras, etc., you get it, that sort of thing.” As the narrator continues, it is almost as if they remember in the moment of their writing this one specific image of the raccoon. “The only animal which has remained lingering in my memory is the raccoon.” Their writing comes across as very organic and honest. Even though memory has all sorts of problems, Sebald’s approach is to flesh out those problems and bring them into the light. Only once the problems have been brought to the forefront can we begin to understand and make sense of any memory.

A similar yet distinct way in which memory can be fascinating is when someone cannot actually remember something, but they are sure it is there. Even though the exact memory cannot be pinpointed, the sense is that this is the way it happened. For example, “For halfway up the walls of the entrance hall, as I must have noticed, there were stone escutcheons…” (p. 12) In this case, the narrator is making an assumption about the past based on what he knows now. They might not remember noticing the stone escutcheons, but they are sure that they did at the time. More broadly, while the actual memories cannot necessarily be retrieved, our minds are still good at putting together a picture of what occurred.

Sebald also explores another nuance in the way that memory can function, which is the likelihood that something occurred or the fairly certain memory like, “A corridor not much more than the height of a man, and (as I think I remember) somewhat sloping…” (p. 25) where Sebald calls attention to “(as I think I remember).” By pointing out every instance that the narrator’s memory might not be reliable, Sebald cements the narrator as trustworthy. Another similar example, but in relation to time, is “Once, I think when I was nine, I went away with Elias to a place in South Wales…” (p. 49) In this case, Sebald is demonstrating the uncertainty in memory with regards to the timing of events. The narrator knows that the event occurred, but cannot place it at the correct time. Both of these demonstrate yet another way in which memory is problematic, and by pointing it out, Sebald demonstrates a path forward.

I have mostly focused on the ways in which Sebald demonstrates the narrator’s lack of confidence in many of their memories, and what that says about memory more broadly. While there is a lot more that can be said about the ways in which memory is unreliable, Sebald also discusses how different memories become intertwined. One example early on in the book is, “Over the years images of the interior of the Nocturama have become confused in my mind with my memories of the Salle des pas perdus, as it is called, an Antwerp Centraal Station. If I try to conjure up a picture of that waiting room today, I immediately see the Nocturama, and if I think of the Nocturama the waiting room springs to my mind…” (p. 5) Here, Sebald demonstrates how memories can become entangled like the narrator’s “of the Nocturama” and “the Salle des pas perdus” that when the narrator thinks of one the other immediately comes to mind and vice versa. Not only does the narrator say they are connected, but they give the background and timeline of when both events occurred, providing much-needed context. Yet again, this cements the narrator as reliable. Unlike many, Sebald realizes the narrator’s memories are entangled, further reinforcing their reliability.

Throughout Austerlitz, Sebald uses all sorts of techniques to make explicitly clear that memory is uncertain. In fact, radically uncertain. Sebald drives this point home time and time again, constantly pointing out things the narrator does not remember, or that they do but in an unconventional way. Given only this, it would seem the lesson to be learned is to not trust memory and to abandon any hope of reconciliation. However, Sebald is not calling attention to the narrator’s flawed memory to show the hopelessness of trying to figure things out, but rather to pave a path forward. Sebald wants to show the reader that while all of our memories are certainly unreliable, that does not suggest a lack of relevant narrative, and maybe the narrative includes the problem of memory. The path forward is not to assume that memory is perfect, but to recognize its flaws and limitations and work within that context.